Rewriting the Story of Aging

There's a story we're used to hearing about aging. A slow, inevitable decline. A journey of loss — of health, independence, identity. This story plays out in quiet corners of hospitals and in loud headlines celebrating the "oldest person to survive" some illness. In clinics, older adults are often defined by what they can no longer do.

But this story is incomplete. And perhaps, even harmful.

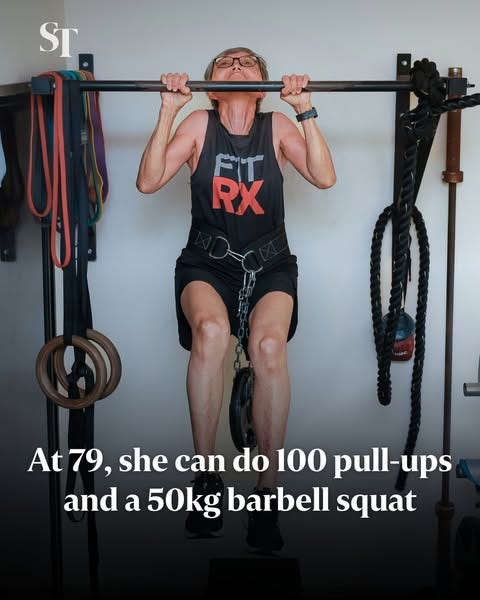

A recent Straits Times article tells a different tale — of Dr Charlotte Lim, 79 years old and able to do 100 pull-ups. She started exercising in her sixties, not after a diagnosis, but because she wanted to feel strong. Now, she teaches others. Her story isn't about escaping death. It's about embracing life.

The Chinese have a saying: 生老病死 (sheng lao bing si) — birth, aging, sickness, death. These are the four inevitable sufferings of human existence. But notice something: aging comes before sickness. It's not the same thing. Somewhere along the way, we've collapsed the two together, as if growing older automatically means growing sicker, weaker, less.

A patient of mine taught me otherwise. I'd known him for over a decade, from my registrar days through to becoming a consultant. We'd chat about our shared history, the Singapore we both remembered, the changes we'd witnessed. He was sharp, funny, opinionated — the kind of person who made clinic days brighter.

The other day, he looked at me and said something that stopped me cold: "Doctor, you and your colleagues have done a good job keeping me alive. But you've forgotten that I used to be a dragon. Now I feel more like a worm. Wouldn't it have been better if I spent more time as a dragon?"

I carried that home with me. The dragon and the worm. The difference between existing and living.

From Lifespan to Healthspan

We talk a lot about lifespan which is how long we live. But what about healthspan — how well we live for as long as we do? This shift in focus isn't just semantic. It changes everything: how we design healthcare, how we support community living, and how we frame aging in our heads and hearts.

The World Health Organization's Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030) reflects this shift, focusing on age-friendly environments, integrated care, and combatting ageism. Locally, Singapore's Action Plan for Successful Ageing calls for lifelong learning, social participation, and community-based supports for seniors.

Programs like Gym Tonic and the Silver Academy aim to redefine what aging can look like in Singapore. The push is no longer just about keeping people alive — it's about helping people stay alive to live life the way they want to.

But metrics alone, even positive ones can't capture what it feels like to age well. For that, we need to listen to the stories people tell about their own lives.

Why Stories Matter

If you want to understand how people age, ask them. Then listen to their stories.

In the Nordic countries, researchers like Sarvimäki have used narrative interviews to explore what aging well meant to older adults. The findings? It wasn't just about mobility or memory. It was about meaning. Being seen. Being heard. Feeling that your life still had value — to yourself and to others.

Narratives don't just describe aging. They shape it. As Chapman notes in his work on aging well, life isn't a static arc but a dynamic story in which older adults continue to make sense of who they are. "Aging well" is a process of ongoing self-integration, not the absence of disease.

This idea — that aging is lived as story — shows up globally. In Canada, researchers explore how digital storytelling empowers older adults to reflect on their lives, leave a legacy, and stay connected to their communities. Participants often reported not only increased well-being, but a stronger sense of purpose. The digital space, far from being intimidating, became a stage for dignity.

In Switzerland, researchers captured the lives of older women through a documentary project focused on hope and self-determination. It's not that these women avoided hardship — they framed it within narratives of resilience, continuity, and learning.

This emphasis on narrative isn't just academic. It's transformative. The Narrative Medicine movement teaches clinicians to attend to the whole story of the patient, not just the part that makes it into the chart. Listening to older patients talk about the food of their childhood, their first job, or their love life may not change their medication dose — but it will change how you see them.

And how they see themselves.

Closer to Home: Stories from Singapore

In Singapore, the stories of older people are too often reduced to headlines or HDB policies. But look more closely, and you'll find them in poetry groups, cooking clubs, Facebook livestreams, and karaoke nights. My own grandmother, in her 90s, uses 小红书 (Rednote) better than I do.

We're slowly creating more platforms for these voices. The Silver Arts Festival, Project Silver Screen, and Arts Fission's creative movement workshops are embedding expressive arts into aging. These aren't just recreational activities — they're acts of narrative restoration.

Why does this matter?

Because qualitative narratives offer insights that quantitative data simply cannot. Research based on biographical interviews with older adults reveals how health experiences are deeply embedded in personal context, identity, and meaning-making. A fall isn't just a fall — it might symbolize loss of independence, fear, or even relief (someone finally noticed me). These stories matter, especially when we're designing policy or care plans.

This explains something that puzzles many of us in healthcare: why do so many elderly patients refuse to use the walking frames or sticks prescribed by physiotherapists? My own grandmother refuses to use one. My patients will often hobble in without their prescribed aids, or fashion makeshift ones from umbrellas. We wonder why they're so stubborn.

But maybe we're asking the wrong question. Instead of "Why won't they use it?" perhaps we should ask "What does using it mean to them?"

In a culture that equates aging with decline, a walking frame isn't just a mobility aid — it's a symbol. It's a public declaration that you've crossed some invisible line from independent to dependent, from capable to needy. It's the difference between being seen as someone who still has a story to tell versus someone whose story is winding down.

When we reduce this to "non-compliance" or "stubbornness," we miss the deeper narrative at play. These aren't just medical decisions. They're identity decisions. They're about holding onto whatever dragons remain.

Many of my older patients tell me they rarely see themselves in stories that aren't about dying or surviving. "What about those of us just living?" one asked. That question stays with me.

What If We Rewrote the Script?

What if healthcare wasn't just about metrics and medications, but also about metaphors?

What if hospital discharge summaries included one line about what the patient loved doing? ("Mr. Lim hopes to get back to his Saturday chess games.") What if waiting room posters featured quotes from older adults reflecting on what they've learned, rather than just instructions for colonoscopy prep?

What if, in training future doctors, we taught not only anatomy but also narrative competence?

Because aging well isn't just about muscles and memory. It's about mattering. And that's something you don't measure with a blood test.

My dragon-turned-worm patient isn't asking for immortality. He's asking for dignity. For the chance to feel, even briefly, like himself again. To roar instead of just breathe.

Let's Tell Better Stories

We cannot stop aging. But we can stop telling it like a tragedy.

生老病死 — birth, aging, sickness, death. These are the stages, but they don't have to be the story. Between birth and death, there's a whole life being lived. Between aging and sickness, there's space for dragons.

Aging is not the absence of youth. It's the presence of something else — depth, perspective, absurd humor, and the ability to wear loud prints without caring what anyone thinks.

Let's talk less about expiration dates and more about expression. Let's celebrate those still learning, lifting, dancing, failing, hoping. Let's train ourselves — as doctors, children, neighbors, citizens — to ask better questions and listen for longer answers.

Let's move from lifespan to healthspan. And let's tell stories that reflect not just how long we live, but how fully we do. Because everyone deserves the chance to be a dragon and we should try to keep them one for as long as possible.

Resources & References

WHO Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030):

MOH Singapore – Action Plan for Successful Ageing (2023): https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/reports/action-plan-for-successful-ageing

C3A Silver Academy: https://www.c3a.org.sg/silveracademy

Sarvimäki, A. (2015). Healthy Ageing, Narrative Method and Research Ethics.

Chapman, S. (2005). Theorizing About Aging Well: Constructing a Narrative.

Cretten, H. et al. (2017). Narrative Gerontology and Digital Storytelling.

Riva-Mossman, S. & Verloo, H. (2017). Explorative Healthy Aging Through Life Course Narratives.

Carpentieri, J. D., & Elliott, J. (2013). Understanding Healthy Ageing Through Narratives.

Straits Times article on Mdm Lee: https://www.straitstimes.com/life/at-79-she-can-do-100-pull-ups-why-more-seniors-are-hitting-the-gym

Dr. Victoria Ekstrom is a consultant gastroenterologist at Singapore General Hospital and co-lead for Narratives in Medicine at the SingHealth Duke-NUS Medical Humanities Institute. Her work explores the intersections of clinical practice, communication, and the human stories that shape healthcare.