The Biopsychosocial Model: How to Actually Use It Without Losing Your Mind (Or Your Patience)

Last week, I shared a post breaking down the biopsychosocial model—you know, the one that encourages us to treat patients as whole humans, not just walking diseases. The feedback? A lot of “Yes, Vic, it sounds all fine and dandy, but how do I actually do this in real life?” And fair enough! So, here's the practical guide, written together with Dr. Andrew Ong, a colleague who does great work with disorders of brain-gut interaction (previously known as functional gastrointestinal disorders).

Firstly, we have to believe that taking a good psychosocial history and applying the biopsychosocial model in patient care is a skill that can be taught, learnt and practiced. In fact, over time it can be done efficiently even in a busy clinic setting. However, like any skill, it does not just happen, but they have to be intentionally sought and practiced repeatedly.

The biopsychosocial approach is even more important in chronic illnesses, where there are often different expectations for diagnosis and treatment between patients and physicians.

Broadly speaking, applying the biopsychosocial model involves seeing the patient and not the disease by understanding the patient’s illness in the context of their psychosocial situation, as the latter will affect the former, and vice versa. To do this, one needs to

1. Interview the patient well to extract the psychosocial information,

2. Interpret it in the context of the illness and then,

3. Integrate it into an effective treatment plan. Let’s see how this works practically in the breakdown of these steps.

Here’s the thing: while this framework is great, it’s not a one-size-fits-all approach. You’ve got to tailor it to your patient group—whether it’s an elderly ah ma or a younger patient in their twenties. My examples might sound weird if you tried them on a 60-year-old auntie, but that’s because I work with a lot of teens and young adults. So yes, you’ll learn how to adapt it and tailor your tone. And please, for the love of all things holy, do not ask, “How is this affecting your quality of life?” That's medical lingo we understand, but patients? They’ll be like, “Huh?” But we’ll save the “stop talking like a doctor” topic for another time.

Step 1: (Interview) Ask Questions in 3 Key Areas (Without Sounding Like a Robot)

To take a proper psychosocial history, you need to dig into three main areas. Here's how to do it:

A. HOW is it Affecting Their Life? (Quality of Life)

Instead of the stiff, “How is this affecting your quality of life?” try something a bit more relatable. If you're talking to a 20-year-old, ask: “How is this messing with your daily routine?” That opens the door to hearing about things like missed work, school, or even their social life. Patients often feel like they need permission to share how their illness impacts them emotionally and functionally (Leventhal et al., 1984). Another easy to use open-ended question like, “How are your symptoms affecting you?” can open up a lot of comments from the patient.

B. WHAT Do They *Think* Is Happening? (Cognitive Process)

What patients do is often influenced by what they think, which is further influenced by what they believe. Patients have theories. Boy, do they have theories. Sometimes, they think they’ve diagnosed themselves better than Dr. Google ever could. Ask them what they think is going on: “Have you thought about what may be causing all this?” and “Anything in particular you are concerned about?” Their answer can give you a peek into their anxieties or misconceptions. This is an easy way to uncover their fears and misconceptions and correct them gently when needed.

C. What Have They Changed Because of It? (Illness Behaviours)

Now, figure out how they’ve adapted their life. Have they stopped socializing? Are they cutting out foods that might not even be a problem? Ask, “What have you tried to change since your symptoms started?” These illness behaviours often perpetuate the problem, and it’s crucial to uncover them so you can help guide patients in healthier directions (Barsky & Borus, 1999).

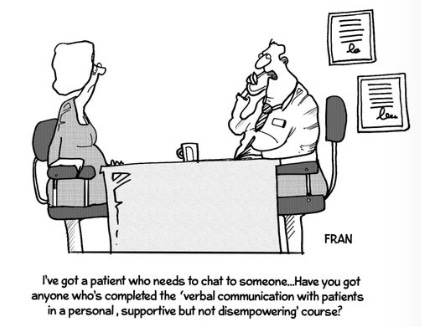

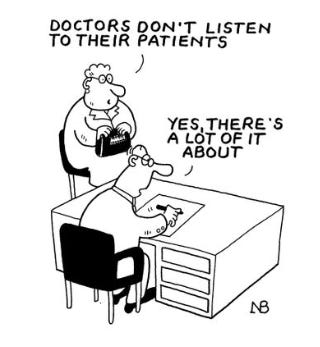

A note of caution is none of these steps matter if active listening principles are not applied. Listening is hard work and is an active process. Listening has 3 parts. What you hear, the respectful engagement (especially non-verbal part) and what you say back (not all the time though) to the other person to demonstrate your listening. This is an active choice, not passive which we will elaborate in Step 3.

Remember, tailor these questions to your patient group. What works for one person might be totally off for another. The key is not to sound like a checklist, but to connect. This takes practice, so don’t stress if it feels awkward at first.

Step 2: (Interpret) Organize What You’ve Learned (Like a Pro)

Once you’ve asked the right questions, it’s time to categorize the patient’s history into predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors:

Predisposing Factors: Things in the patient’s past that have made them more vulnerable, like chronic stress or a family history of mental health issues (Barsky & Borus, 1999).

Precipitating Factors: What triggered this? A divorce? Job loss? Maybe a viral illness was the last straw (Engel, 1977).

Perpetuating Factors: What’s keeping the symptoms going? These could be behaviors like avoiding certain foods or fear of socializing. By figuring this out, you can help break the cycle.

Just remember, not every patient needs this level of psychosocial history. Sometimes a simple medical history is enough, but knowing when to go deeper is a skill.

Step 3: (Integrate) Tailor the Treatment (Without Losing Their Trust)

The goal of approaching the patient biopsychosocially in the managing chronic illness is to help them regain control over their illness and their life. On one hand, we need to provide clear physiological explanation to the patient to help them understand their condition, but more importantly we need to help patients find ways to accept their illness and learn to self-manage.

Now that you’ve sorted through the patient's history, you can start to develop a treatment plan that actually addresses how they think, feel, and act. The key here is to adapt your communication to suit the patient.

1. Address Their Illness Behaviours

Avoidant behaviours rarely help the patient move forward in self-management of their illness. If the patient is avoiding all social activities or cutting out entire food groups unnecessarily, work with them to reintroduce healthy behaviours. You’ll likely need to go slow, but it makes a huge difference (Sharpe & Bass, 1992).

2. Reframe Their Cognitive Distortions

A lot of patients have unhelpful thoughts, like “This illness is going to ruin my life.” Help them reframe that thinking with cognitive restructuring techniques (Beck & Haigh, 2014). Maybe it’s not about “curing” them but finding ways to manage the symptoms better. The cognitive distortions can be very complex and require interventions from a psychologist, but making this first step often builds the bridge for an effective therapeutic relationship with patients and healthcare providers (e.g. physicians, psychologists).

3. Communicate Like You’re Human

This is where narrative medicine shines. You’ve got to show empathy. You’d be surprised at how much better patients feel just by being heard. Sometimes it’s not about fixing them right away, but just validating their experience (Beck & Haigh, 2014).

The cornerstone to empathetic communication is genuinely understanding & validating the other person’s feelings and then communicating that understanding back to the individual.

A useful skill is “anchoring” where we can use what has been said to be reflected back to keep the conversation fluid and moving forward while reminding the patient they are being heard. This also allows connecting what they said to what we are going to say. So, if a patient tells you their life has been wrecked by the newly found lactose intolerance, you can respond by saying “It’s tough not to be able to drink milk because of these new symptoms you have, especially if you have loved milk since young, but there are ways we can go around this and you don’t have to avoid milk completely. We can do these….”

But Not Every Patient Needs the Full Treatment

For the younger ones who haven’t watched Scrubs (recommended watching for everyone), this is Dr. Bob Kelso!

Here’s the thing: The biopsychosocial model isn’t necessary for every patient. Some just want quick solutions. The real skill comes in knowing when to dig deep and when to keep it simple. And that takes time to master.

Watch and Learn

If you’re more of a visual learner, check out this video on how to have a better conversation.

Final Thoughts: Tailor Your Approach, Keep It Real

So, here’s the gist: you have to tailor your questions and approach to each patient. Whether it’s an elderly ah ma or a younger patient in their teens, practice will help you figure out the right balance.

It is way easier to perform costly tests and prescribe empirical symptomatic treatment without making the effort to understand the patient. However, managing chronic illness will not move forward doing these.

The skills described above are not learnt from textbooks but by observing those who practice it. But it also requires reflection and learning from one own’s experience, and ultimately, a genuine desire to help the patient.

Our goals when managing chronic illness with the biopsychosocial model often transition into building relationships with the patient to help them help themselves, whilst expecting only occasionally to cure them completely.

And yes, this post is a direct response to the feedback from last time, where people were like, “Vic, this sounds great in theory, but how do I actually do it?” Well, this is how! Now go out there and practice!

References

Barsky, A. J., & Borus, J. F. (1999). Functional somatic syndromes. Annals of Internal Medicine, 130(11), 910-921. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-130-11-199906010-00016

Beck, A. T., & Haigh, E. A. P. (2014). Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: The generic cognitive model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153734

Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129-136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

Leventhal, H., Nerenz, D. R., & Steele, D. J. (1984). Illness representations and coping with health threats. In A. Baum, S. E. Taylor, & J. E. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and health (Vol. 4, pp. 219-252). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Andrew Ong is a gastroenterologist who strongly believes that wherever the art of medicine is loved, there is also a love for humanity as per Hippocrates. He runs the weekly SGH psychogastroenterology clinic, integrating medical, psychological and dietary interventions to patients with IBS and other similar disorders of gut-brain interaction.

Victoria Ekstrom is a regular contributor to HEART and is delighted to have a co-author joining her on this piece—it's always nice to share the stage (and give readers a little break from just her voice)!