The Biopsychosocial Model: Rethinking How We Approach Illness

Modern healthcare is moving at lightning speed. With clinic consultations that sometimes feel shorter than a Netflix intro, we’re squeezing diagnosis into ever-tighter timeframes. Doctors, overwhelmed by tight schedules, often rely heavily on diagnostic tests to guide their decisions. And while those tests are incredible for revealing structural abnormalities—what we refer to as disease—they fall short in addressing the complex human experience of illness.

The difference between disease and illness is critical. Disease is about measurable, verifiable abnormalities in the body, such as a broken bone or a tumor that shows up on a CT scan. Illness, on the other hand, is the personal experience of feeling unwell, and it often includes a combination of physical, emotional, and social components. You might have a patient who’s perfectly healthy on paper, but their experience of illness is profound and real.

Solomon, Miriam et al. “DISEASE, ILLNESS, AND SICKNESS.” (2018).

Take, for example, a patient with chronic pain. The tests might come back normal, showing no structural issues. But the pain they experience is very real to them. When patients present with symptoms that can’t be explained by test results, they are often left feeling dismissed, like their suffering isn’t valid because it doesn’t fit within the traditional biomedical framework.

The Legacy of Mind-Body Dualism: Blame Descartes!

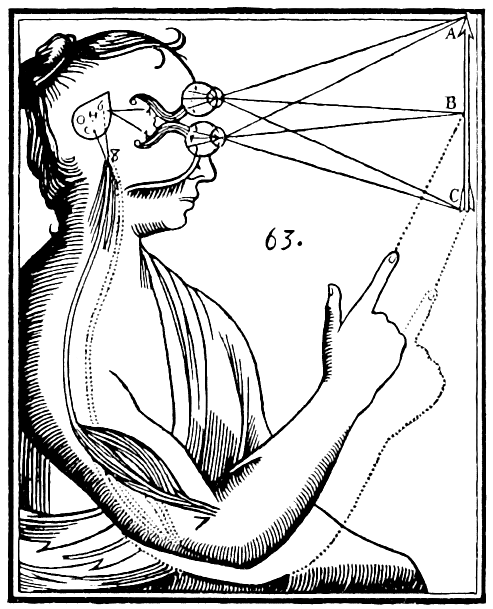

So why do we struggle with this difference? Let’s take a time-traveling detour to the 1600s and blame René Descartes. Descartes was a big believer in mind-body dualism, the idea that the mind and body are two separate things. He thought the mind was something ethereal and untouchable, while the body was a physical machine we could poke, prod, and dissect. Descartes’ ideas were a big hit and became the foundation of Western medicine, which started focusing almost exclusively on the body’s physical problems—leaving the mind and emotions as afterthoughts.

Illustration of mind–body dualism by René Descartes. Inputs are passed by the sensory organs to the pineal gland, and from there to the immaterial spirit.

And that worked... for a while. The biomedical model built on Descartes’ dualism works beautifully when you’ve got something straightforward like an infection. Got a bacteria? We’ll blast it with antibiotics. Problem solved! This one-cause, one-fix approach has been the gold standard for treating disease. But what happens when the patient’s symptoms doesn’t line up with what the tests show? Welcome to the wonderful world of chronic illness, where structural abnormalities (or the lack of them) don’t always explain the pain or suffering someone feels.

Enter the Biomedical Model: Great for Bacteria, Bad for Chronic Pain

Let’s take an example I often see in gastroenterology: two patients with similar diagnoses, but vastly different experiences of pain. One patient might not feel any discomfort until their condition worsens to the point of perforation, while the other patient experiences excruciating pain even though tests show nothing abnormal. What’s going on here?

The answer lies in how each person processes pain, both physiologically and psychologically. We now know that the mind and body are not separate at all. They are intricately connected. When a person experiences emotional distress, it can manifest as physical symptoms—chronic pain, fatigue, gastrointestinal issues, and more. The biomedical reductionist approach doesn’t account for the vast differences in how individuals experience and respond to illness. It doesn’t explain why one person feels pain while another doesn’t, even though their bodies might look the same on a scan.

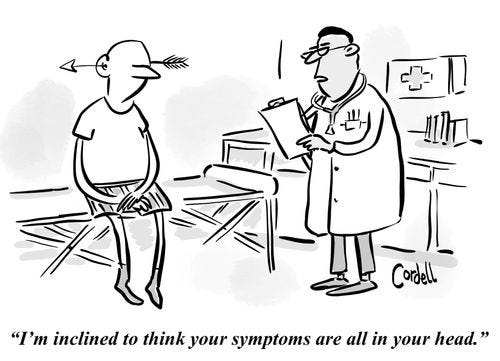

The problem is that dualism has left many doctors trained to look for physical pathology only. And when they can’t find it, they often struggle to explain the patient’s symptoms. For instance, imagine a patient with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). They undergo a colonoscopy, and it comes back normal. There’s no evidence of structural damage, yet they suffer from debilitating abdominal pain. The doctor, trained in the biomedical model, might struggle to validate the patient’s experience because, in this model, if there’s no visible abnormality, there’s no disease. But here’s the reality: not all illnesses are structural. Some illnesses are rooted in the mind-body connection, in stress, trauma, and emotional turmoil.

The Vicious Cycle of Frustration when there is Illness without Disease: Why No One’s Happy

When patients come in with symptoms but no clear structural cause, they often find themselves caught in a vicious cycle. The doctor orders tests, hoping to find something. When the tests come back normal, the patient feels dismissed: “Doctors don’t believe me.” They may seek second or third opinions, or they might intensify their requests for more tests, desperate for a diagnosis that validates their suffering.

On the other side, doctors feel the pressure too. If there’s one thing doctors hate, it’s uncertainty. We’re trained to solve problems. Patients come to us with symptoms, and we’re supposed to figure out what’s wrong. But what happens when the tests say everything’s fine, yet the patient is still in pain? We like answers. We want to help, to provide a diagnosis, to offer a solution. And when we can’t find a physical problem, we can feel like we’re failing. We want to help, but without any clear structural abnormality, we feel uncertain.

The reality is, though, that not all illnesses can be explained with a test. We find ourselves stuck between uncertainty and discomfort. As Elaine Scarry wrote in her book "The Body in Pain", “To have pain is to have certainty; to hear that another person has pain is to have doubt.” This sense of uncertainty is deeply uncomfortable for doctors who are trained to identify and fix problems. Some become defensive, frustrated, or even withdraw from the process altogether. Some may refer the patient to another specialist or quietly imply that the issue is psychosomatic.

This dynamic leads to disillusionment on both sides. The patient, feeling ignored and invalidated, continues to suffer. The doctor, unable to provide answers, becomes more withdrawn, and the relationship deteriorates. Safety and outcomes can be negatively affected when doctors and patients fall into this trap. Cue the vicious cycle of dissatisfaction.

Breaking the Cycle: Enter the Biopsychosocial Model

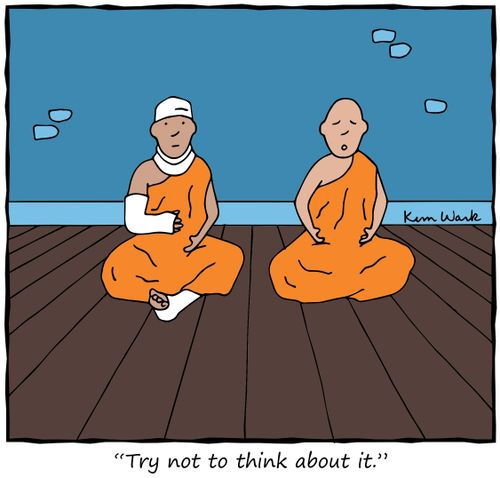

Here’s where we cue the hero music for the biopsychosocial model. This approach throws out the idea that illness is purely physical. Instead, it embraces the messy, beautiful complexity of the human experience. Illness isn’t just about what’s happening in your gut, your brain, or your joints. It’s also about what’s happening in your mind, your relationships, and your environment.

The biopsychosocial model encourages doctors to listen to the patient’s story, to ask questions about their stress, their trauma, their emotional well-being. It gives us permission to move away from the rigid biomedical model and embrace a more patient-centered approach. Sometimes, the solution isn’t in a pill or a procedure—it’s in understanding what’s going on in the patient’s life beyond the clinic.

Narrative Medicine: Where Stories Heal

Here’s where narrative medicine comes into play. This concept isn’t just about fixing what’s broken; it’s about listening. When patients tell their stories, we start to see the bigger picture. We hear about the stressors in their lives, their emotional struggles, their support systems (or lack thereof). We begin to understand their illness beyond what an X-ray or blood test can reveal. Narrative medicine asks us to slow down and take the time to hear these stories because in those stories, we often find the answers that tests can’t give. We need to learn to sit with that discomfort, to embrace the unknown, and to understand that sometimes the patient’s story—their narrative—is just as important as the scan.

Further Learning: A Holistic Approach to Medicine

If you’re interested in exploring more about the connection between mind, body, and illness, here are a couple of YouTube videos to get you started:

It’s a great introduction to understanding why the biopsychosocial model matters in healthcare today.

If you’re into the power of storytelling, this is a must-watch. It shows how stories help bridge the gap between what we see on a scan and what the patient feels.

Final Thoughts: Embrace the Uncertainty, Validate the Pain

In the end, patients want more than a diagnosis. They want to be heard. They want to be believed. As doctors, we have to recognize that illness is so much more than a test result. It’s a complex interplay of the mind, body, and environment. And while we might not always have the answers, we can always provide empathy, validation, and a willingness to listen.

It’s time to move away from the rigid structure of biomedical reductionism and embrace the biopsychosocial model. By doing so, we not only help our patients feel better—we might just help them feel seen.

Victoria Ekstrom is a gastroenterologist by day and a K-drama addict by night—or at least during the rare quiet moments between her two small children’s demands. As co-lead of the Narratives in Medicine arm at SingHealth Duke-NUS Medical Humanities Institute, she’s constantly searching for ways to bring storytelling into clinical practice.